Friday, July 5, 2024

how to get a little more done each day by eliminating productivity dead zones

Monday, April 1, 2024

Try the "do it tomorrow" method - it's not about procrastinating!

The relief was realizing that I had a chance to complete my list for today.

This feature is consistent with advice from productivity expert Mark Forster in his book Do It Tomorrow: when a new task appears during the work day, add it to a list "to do tomorrow."

You may be thinking, but what happened to "do it now"?

It's still a thing!

But it should not be used at the expense of the tasks you have planned to do today, unless there is a convincing reason to do it today!

The science behind do it tomorrow.

The Do It Tomorrow method helps combats the "mere urgency" cognitive bias, which says that your brain interprets any new task as urgent, even thought you really know it is not.

By having a plan to automatically add new tasks that are not truly urgent to the tomorrow list you are honoring the urgency you feel in the moment - and as you will be putting it on the list in a place you can see it, you can always change your mind.

How to use the do it tomorrow technique.

Start with making a task plan for today - you can read about that here

Then, when a new task pops up during the work day, ask yourself if it can be safely deferred to later. If it can, add it the "do it tomorrow." If you finish today's tasks early, you have my permission to work ahead!

Here is a model of a paper daily task plan you can use to design your own on paper or in a task app:

>

Note: The Do it Tomorrow list does not literally mean you will do it tomorrow!

Instead, it give yous a cooling off period to more realistically assess the items actual priority, and from that, when it really should be done.

That's it. Give it a try.

Saturday, May 20, 2023

A weekly review and plan starter kit

"It is surprising how much I can get done when I take enough time for planning, and it is perfectly amazing how little I get done without it." ---Frank Bettger, How I Raised Myself from Failure to Success in Selling," 1947

Every productivity expert I know recommends spending time planning the coming week.

Yet few people do it.

Why? "Time."

Even the tiny amount of time required for a basic review, half an hour or so, seems like "too much" when you think you could be doing real work.

But there is a BIG payoff.

You have more things to do than you can do in the next week.

Making a plan helps you choose the right work to fit the available time. Having personally experienced the tremendous benefits of this process, I want you have those too.So here is a simple "stripped down" weekly review and planning process that I hope you will be inspired to try,

Get a sheet of paper and at the top, write "review & plan for week of <date>."

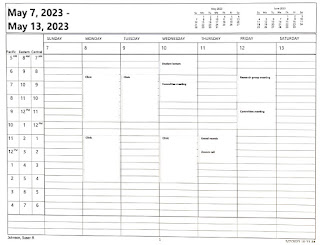

Open up your calendar in week view.

Look at each scheduled event for each day, and ask, "Do I need to do anything to prepare for this?

If there is, add it to your sheet of paper.

When you are done with Monday - you guessed it! - look at Tuesday and on through the week.

Now look at the next 3 weeks (or farther out if you like),

Scan for upcoming deadlines, big meetings, or other events that you should start preparing for in the coming week.

If there is, add it to your sheet of paper.

Gather all the places where you store "to do's."

The "places" could include task lists, a whiteboard, a notebook or legal pad, a bunch of post-its, notes on your calendar or phone app, or your email inbox.

If that sounds complicated, think about starting a master task list, and then you only have to "gather" one thing🙂.

If you store things in your memory😞 get a second piece of paper, and spend a few minutes writing them down.

Read each item from each location.

For each, ask "Is this something I should complete or start to work on this week"?

If an item will take an hour or more, consider putting an "appointment with yourself" on your calendar, or what is now commonly referred to as a time block.

That's it.

Will you get them all done? Possibly not.

Actually, probably not. But as you repeat this process over time you will get better and choosing a more realistic amount of work to fit the available time.

There are other things you can add to make your plan even more effective, but that's for another day.

Monday, April 24, 2023

Yes? No? Maybe so? Ideas for thinking about whether to say yes or no to new work.

Time is the coin of your life. It is the only coin you have, and only you can determine how it will be spent. Be careful, lest you let other people spend it for you. - Carl Sandburg

Next week, I'm facilitating a session at a national meeting about the ins and outs of deciding when to agree (or not to agree) to take on new work.

It's a topic I know well from many years - actually, decades - of saying "yes" more often than I should have.

While the ideas are top of mind, I wanted to share them here.

The process has two pieces: making a decision and then sharing it with the asker.

I'm going to focus on the first part here. The better your decision-making process, the better your decisions, and, the easier it it to say "no" when you need to.

Between the ask and the response, there is space - use it!

- Does this thing fit with your interests and/or goals?

- Is there something else you will get from doing this that is valuable, like learning a new skill or expanding your network?

- How heavy is your current workload? Is there really time to do this new thing? If you're not sure, make a list of everything you are doing. (If that sounds horrifying, you already know the answer...)

- Don't be fooled by "the empty future calendar" bias. This happens when the deadline is distant, and your calendar at that time looks open. Better to assume you will be just as heavily scheduled then as you are now.

- Is there anything you currently do that you could give up, delegate, or defer to later?

- If your boss is asking, can you negotiate about some of your current work?

"The hallmark of a decision in line with one's character is ease and contentment and an ample, even provision of natural energy." - Anne Truitt, Turn: the Journal of an Artist

Assign "yes" to one side of the coin and "no" to the other. Flip the coin.

How do you feel about the decision that is revealed? Do you feel relief or disappointment for a "no?" Does a "yes" lead to "ease and contentment and... energy" or stomach-turning anxiety?

I know this sounds like a transparent trick, but it actually works!

And finally, if it's a big decision, write about it! Don't just think! The act of writing will lead to questions, feelings, and reasons that you might otherwise miss.

Wednesday, February 1, 2023

My New Year's treat: One practice that helps you keep on top of your work.

1

My new year's advice.

On January 11 - at the right time for new year's resolutions - I posted this:

Hi Susan,I wanted your advice about creating goals or a schedule for the week, such as what you want to accomplish that week. I've been following Cal Newport since we worked together, and I'm working on my time-blocking for the day.However, I struggle to get a "big picture" look at the week, or it comes to the end of the week, and I realize I made no progress on something I wanted. I feel like making a weekly plan is something I should do, but I'm unsure where to start.Thanks, Steven (NHRN!)

Steven,

The core practices are to review and update your calendar and todo lists (for me, my project and master task lists), and then select some high-priority work to fit into the week.

Here's a checklist to help you get started....

- Add any scheduled events that did not get recorded.

- Look at each scheduled event, and ask:

- Do I need to prepare in advance?

- Do I have all the information I need (meeting location, zoom link, phone phone number, the agenda, the plane tickets)?

- Add up the unscheduled time during work hours. Assume that at least half of that time will be needed for routine work and interruptions. The remaining amount is the most time you will have for project work and other important tasks.

- Read through your project list and pick the ones you want to work on in the coming week. Consider deadlines, importance, and the available time you just estimated.

- For each selected project, write a few sentences about what you want to accomplish. I learned this method from Cal Newport, and I find that this narrative format helps my thoughts flow so that end up with a better plan than when I just make bullet points.

- For each project, create at least one task and/or schedule a time block.

- Read through your task list and adjust as needed: delete completed tasks, revise unclear tasks, and add new tasks that you think of.

- Select critical tasks for this week and move them to the top in your list app. (Or if you're on paper, write a weekly list).

"You can do the core process I've described in about 30 minutes, or less.Do you have 30 minutes sometime between Friday noon and Monday morning?"

"It is surprising how much I can get done when I take enough time for planning, and it is perfectly amazing how little I get done without it."----Frank Bettger, How I Raised Myself from Failure to Success in Selling, 1947

Wednesday, December 7, 2022

The daily task plan: how to pick your MITs

I’ve written before about the benefit of making a short daily list of high-priority tasks that you will aim to do in addition to your regular work and before other items on your master to-do list. This type of list is sometimes referred to as a “Most Important Task” list (MIT).

In that original post, I gave a short list of criteria to help you pick your MITs. Since then, I’ve added a few more, so an update is due.

Three criteria by way of Captain Obvious.

Tasks related to your high-priority work.

Examples:

- Drafting the discussion for a paper.

- Finalizing arrangements for the conference you are organizing.

- Revising the PowerPoint slide deck for next week’s talk.

Tasks that have a "hard" external deadline of today.

Examples:

- Today is the last day to submit the application for a leadership program.

- Your VISA bill is due today and you don’t want your credit rating to suffer by being late.

Tasks that you have promised someone you will do by today.

Examples:

- Bake brownies for the first-grade class.

- Send comments on the manuscript.

- Really, anything you have promised to do, and there is no longer time to renegotiate your agreement.

Two criteria that are not so obvious.

Tasks that start a chain of events leading to an important outcome later.

Examples:

- Sending your travel expense to get reimbursement more quickly so that you can minimize credit card interest

- Starting the IRB application process at the beginning of a project, even though approval will not be needed for several months.

- Emailing your friend in North Dakota to see if she will be there when you visit the area in 3 months.

Tasks that will prevent the need to do something else over and over in the future.

Examples:

- I recently took the time to research, install and set up the Calendly app, which allows my coaching clients to set up sessions on their own. Now I save the time I used to spend going back and forth by email to find times to meet and then creating outlook invites and zoom links. I’m so happy!

- Taking the time to delegate a task to someone else so that you don’t have to do it anymore.

One criteria that may be controversial, but I stand by it!

Tasks you have been putting off that you are so stressed about you don’t think you can focus on anything else.

- Once I do such a task, I can peacefully move on to the "real" important stuff.

- The risk: Using as an excuse to do a series of tasks that are small or easy that you are not stressed about so that you never get to the rest of the MIT’s.

- The rule: You only get to put one of these in the MIT list per day!

Sunday, November 20, 2022

Not motivated? Try the assembly line approach.

Last week I looked at my task list for the day and then looked away.

I just didn’t feel motivated.

But I had a backup plan!

I returned to the list and set a goal of completing the entire thing.

To get started, I read the first task and then worked through it until completed.

Then I went to the second one on the list and did the same thing.

And so on, in the order listed, until every task was complete.

Why did this work?

I knew that if I took action, no matter how slight (in this case, simply reading the task), my “motivation” would return.

It’s the cognitive equivalent of Newton’s second law: “A body in motion remains in motion.”

Taking action is what leads to motivation, not the other way around.

I call this strategy the “assembly line” approach. It is my nearly no-fail way to work when I don’t feel like doing anything or when I’m avoiding specific tasks.

How does this work?

Think about how a real manufacturing assembly line works.

The outcome of an assembly line is a product: a car, bottles filled with ketchup, and so on. A switch that turns on the moving belt has to be flipped to “on.” Once the belt starts, the unfinished product moves down the line to the next station to be worked on.

My task completion assembly line has these same components:

First, I decide on a product, usually a defined batch of tasks to complete.

Then I take an action that switches my mindset from “not working” to “working.”

When I complete an item, I use a predetermined rule to move to the next one without having to think.

Step 1. Define your product

A “product” for this method is a completed batch of work.

I use this method for any kind of batched work, including a short list of tasks, new mail messages, email messages I have been avoiding, phone calls, routine paperwork, and clearing up papers haphazardly strewn around my workspace.

Step 2: Take action to "turn on" working.

When I am unmotivated, I need an initial action that requires no thinking—akin to flipping the “on” switch for the assembly belt.

Pick something for which you feel no resistance at all. In my task list example above, my first task was to continue revising this post! My no-resistance action was to copy and paste the text I had already written in Evernote (my note-taking app) into Scrivener (the app I use for final drafting).

I use a variety of these no-resistance actions. Among them: copying my last paragraph to start work on a writing project, opening the app I need, moving from the kitchen to my home office, or setting my Pomodoro app timer.

Each of these signals to my brain that it’s time to work.

Step 3. Decide on a method to move from one item to the next.

Mark Forster first introduced this idea by recommending the use of a "mechanical" method to decide what task on your list you to do next.

This eliminates the time spent ruminating (in my case at least) about “What’s the very best next task?”

When working from a task list, I just go to the next task on the list.

(Here’s another example. Close your eyes, put your finger on the list - best done on paper! - and do the task you are touching. Or put the list on a dart board, and have at it!)

Here is my assembly line process for four kinds of work to give you some ideas.

Tasks

Product: Tasks on a defined list completed. For example, my “MIT” list (the 3 most important tasks for the day) or a set of tasks I have been putting off.

Papers strewn about my workspace

Product: All the papers in the stack handled (recycled, filed, added to my task list, or the required task completed).

New email messages

On switch: Open my email app.

Mechanical rule. Start with the most recent message and then go to the very next one.

So really, who needs motivation when you have a method!